A well-honed Git configuration

By Christophe Porteneuve • Published on 3 April 2013

• 9 min

Cette page est également disponible en français.

Git offers 3 levels of configuration:

- Local. Specific to each local repository, it is stored in the

.git/config. It includes branch tracking, remote definition, etc. - Global. This is user-specific and is stored at the root of the user account, in the

~/.gitconfigfile. This is the one we are interested in here. - System. Usually stored in

/etc/gitconfig, it is shared by all users. It is seldom used.

Priorities run in the usual order: from local to system.

Most users just put in their name, email and editor preferences into their .gitconfig. This is an appalling under-use. There are many, many aspects of Git that can be configured, and therefore improved, through configuration.

This article explores my personal configuration to show you many useful tips.

First of all, make sure you are using a recent Git (1.8+). Many of the configuration options discussed below have only recently been introduced. If an option seems to be ignored in your system, check the name and value carefully, and then look at the release notes to find the version in which the option appeared.

I maintain a generated public version of my configuration in this Gist. By “generalized” I mean that I remove, or comment out, some processing that I think is tricky to enable by default, because it involves subtle Git behaviors that you should know about before applying them.

A Git configuration file is similar in syntax to a good old-fashioned INI file: sections are delimited by a [name.section] header, and the property lines that follow belong to the section. Indentation is recommended but not required. The linearised representation of a property is section.name, e.g. core.whitespace for the whitespace property within the [core] section.

Here is the global gist already:

Let’s now look at these settings one by one.

Default identity for commits

This is as basic as it gets: attributing your future commits. We use user.name and user.email for this. However, don’t mess up the Git config of a deployment user on a production server with this kind of stuff, if there are several people who can deploy. Instead, attribute your commit with git commit --author=... so you don’t alter the settings.

Coloring

Many Git commands are able to colorize their output using ANSI VT codes when the terminal allows it. The auto value has the same meaning as in many other Linux commands (e.g. ls): Git will detect whether it is being used by a VT terminal capable of handling color codes, and if so, will leverage that capability.

The color.ui property is an umbrella setting for all more specific color-handling properties, e.g. color.branch, color.diff, color.grep, color.interactive, etc. Basically, we want colors!

Aliases

Git only allows full command names by default (commit, checkout, etc.), which sometimes makes Subversion users cringe when starting with Git, searching in vain for their git ci. Apart from the fact that a properly configured prompt will offer advanced completion (that’s a topic for another post), the real reason is that Git lets you create as many aliases as you’d like, using the settings in the [alias] section. Each property is named after the alias, and its value is the Git command line without the leading git.

My configuration provides 3 aliases I couldn’t work without:

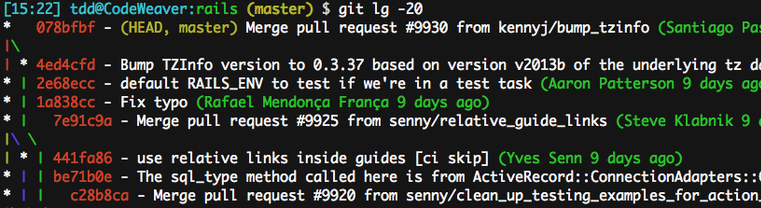

cifor commitstfor statuslgfor advanced contextual log which, as far as I’m concerned, is just as good as graphical logs (branch graph and merges, symbolic references, tags and branch heads, SHAs, authors and relative timestamps). As a bonus, it works in a terminal, hence via SSH…

Pagination, whitespace and other “core” settings

By default, Git paginates everything it displays: if it exceeds the height of the terminal, it uses less. Personally, I can’t stand that: if I want to paginate, I | less myself! By specifying via core.pager to go through cat rather than less, I de facto disable paging.

When opening an editor (especially for commit messages or setting up an interactive rebase), Git chooses the editor like this:

- The

GIT_EDITORenvironment variable - The

core.editorsetting (my favorite way) - The

VISUALenvironment variable - The

EDITORenvironment variable - The default binary set at Git compilation time; usually

vi.

If the default behavior isn’t your cup of tea, you need to specify the command line to run. When using a graphical editor, you’ll need to invoke it so that it’s in wait mode, meaning that it doesn’t yield back control until the relevant file is closed. Not all graphical editors let you do this.

Here is a list of some command lines!

☝️ If you are on Windows: if your terminal does not recognize the editor opening command, you should consider passing the full path to the executable (this usually depends on the terminal used).

- VSCode:

code -w - SublimeText:

subl -w. - GEdit:

gedit -w -s - GVim:

gvim --nofork - Coda: you will need to setup coda-cli (usually through the always-handy Homebrew) then

coda -w. - Notepad++: you may need to adjust path depending on where you installed Notepad++, but here is the idea:

'C:/Program Files (x86)/Notepad++/notepad++.exe' -multiInst -notabbar -nosession -noPlugin.

Finally, the core.whitespace setting prevents certain types of whitespace differences from being detected or causing problems for commands like git diff, git add -p, git apply or git rebase. There is a whole range of possible combinations; trailing-space is a combo for blank-at-eol (whitespace at the end of a line) and blank-at-eof (whitespace, especially empty lines, at the end of a file). As I am indicating this value here as a negative (note the - prefix), I am making it clear that this type of deviation should not be a concern or reported.

Enhanced diffs

By default, any variant of diff identifies the two versions as a and b :

[15:54] tdd@CodeWeaver:git-attitude (master *+%) $ git diff 2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

diff --git a/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown b/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

index e69de29..44bd5ae 100644

--- a/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

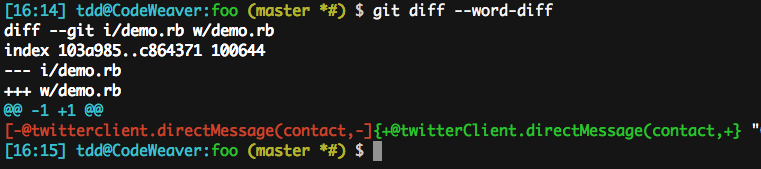

+++ b/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdownIt is not always clear what a or b are… The HEAD? The stage? The working directory? Recently, Git provided a setting, diff.mnemonicPrefix, which when set to true will replace, where applicable, these anonymous letters with three others:

cfor Commit (usually HEAD)ifor Index (our stage)wfor Working Directory

Thus, a regular diff explicitly states that it is performed between the stage (the index) and the working directory:

[16:02] tdd@CodeWeaver:_posts (master *+) $ git diff 2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

diff --git i/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown w/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

index 202f830..cde050e 100644

--- i/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

+++ w/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdownA diff --staged does indicate that it is done between the HEAD (a commit) and the stage (the index):

[16:02] tdd@CodeWeaver:_posts (master *+) $ git diff --staged 2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

diff --git c/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown i/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

index cde050e..202f830 100644

--- c/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

+++ i/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdownAs for a diff HEAD, which makes its reference commit explicit, it confirms that it is comparing a commit and the working directory:

[16:02] tdd@CodeWeaver:_posts (master *+) $ git diff HEAD 2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

diff --git c/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown w/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

index cde050e..3f85496 100644

--- c/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdown

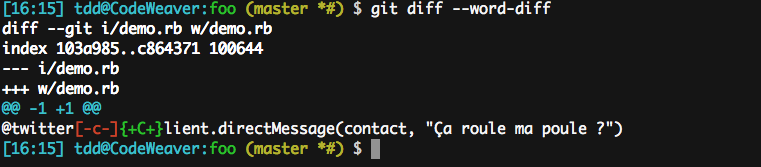

+++ w/source/_posts/2013-04-03-configuration-git.markdownAnother slightly unfortunate aspect of git diff is the default behavior of git diff --word-diff. Whilst it’s nice to have a default word diff mode, which lets you target the area of difference between two arguably very similar lines (much like the contrast change in graphical diff tools), Git defaults to considering any non-whitespace character sequence as “word”. In a block of code, that often creates a long display, since delimiters and operators will also be counted. For example, @twitterClient.directMessage(contact, is considered a word. Sigh.

This is why git diff provides another option, --word-diff-regex=..., which lets you specify a regex representing a “word.” Naturally, reducing this regex to . will attempt the minimal match (down to a single character). In practice, when I do a word-level diff, I always do this.

That’s the whole point of the diff.wordRegex setting: it allows a simple --word-diff to be treated as a --word-diff-regex=.... See instead:

Submodules

For those of you who are caught up in the day-to-day hassles of submodules (there are plenty of pitfalls in their day-to-day use), you can add a few safeguards through configuration:

fetch.recurseSubmodulesautomatically detects during afetch(and thus apull) if the submodule references have moved, and offers to retrieve them automatically if this is the case. Beware, it doesn’t callsubmodule update.status.submoduleSummaryreports withingit statusthe submodules whose references have moved, listing the relevant commit deltas.

Extended regex as default

There are many use cases in Git where you can use regular expressions (regex). These include git log --grep and git log -G, to name a few. By default, however, only BRE (Basic Regular Expressions) are processed, i.e. most special characters such as {}, (), + and ? are ignored. In practice, when I use a regex, I always want to have Extended Regular Expressions (ERE), which enables all possible syntaxes.

Rather than having to add -E to my command line, I enable the grep.extendedRegexp setting in the global configuration.

Beware though: your regexes will not be case-insensitive. If you want to ensure this, you will usually have to add -i to your command lines.

Full SHAs are useless

Most Git commands and documentation pages use abbreviated SHA1s, or abbrevs, the first 7 characters only. The probability of colliding 7-character SHA1 values is infinitesimal (I’m not an expert, but it’s probably as low as 2−132, which means you’re only slightly less likely to run into a particular atom on Earth, including us; sounds like an acceptable risk).

I enabled log.abbrevCommit so that even a bare-bones git log uses that shortened form.

More convenient merges

Whilst Git does provide us with a plethora of mechanisms to best resolve a merge conflict, it is still possible to improve on the default behavior.

For example, Git injects classic conflict markers into text files. For example :

<body>

<<<<<<< HEAD

<h1>This is great</h1>

=======

<h1>This is beautiful</h1>

>>>>>>> feature

</body>It is already possible to get more information at this stage, by displaying between the two (the HEAD branch and the merged branch) the version of the text in the common ancestor (divergence point, or merge base). This is the diff3 mode, which I automatically activate with the merge.conflictStyle setting:

<body>

<<<<<<< HEAD

<h1>This is great</h1>

||||||| merged common ancestors

<h1>This is nice</h1>

=======

<h1>This is beautiful</h1>

>>>>>>> feature

</body>Related: when using a conflict resolution tool (a mergetool), it can generate temporary or backup files (often with extensions like .rej, .orig, .local, .tmp, .bak…), which happily smear your working directory. Even if these extensions are protected from being inadvertently added with a .gitignore or equivalent, the files remain there.

You can ensure that your tool will clean up after itself by disabling the mergetool.keepBackup and mergetool.keepTemporaries settings.

Finally, when you run git mergetool, it prompts by default for confirmation as to which file to open/check. To avoid this often-unnecessary question, disable mergetool.prompt.

Another important topic, on which we also have a detailed article, is ReReRe. This advanced Git feature allows you to save (locally) conflict fingerprints and the manual resolutions you made to them, and then automatically re-use those resolutions later. It’s extremely handy and enables very powerful workflows. You can explore the docs on this topic, and if you wish to use it, just enable rerere.enabled and, if you wish to automatically stage these automated resolutions, rerere.autoupdate.

Rebase your pulls by default

I wrote another article on why I think the vast majority of pulls should use a rebase rather than a merge. Basically, it’s to avoid messing up the history when several people commit to the same shared branch in parallel.

The git pull command is actually a sequence of two more specific commands: git fetch followed by git merge. For example, if you are on master with a default remote of origin, git pull is like doing:

git fetchgit merge origin/master

When you work with several people on that branch, it is usually best to do the equivalent of:

git fetchgit rebase origin/master

Git anticipates this scenario and lets you do this with git pull --rebase. However, I think this should be the general case, not the special case. It has indeed become possible to work this way by enabling the pull.rebase option.

The only pitfall here is that a rebase, by default, “inline” merges. This can be customized when you git rebase manually, but for a long time could not be tuned in the context of a pull. Let’s look at an example.

Let’s say you’ve just done a legit merge on your local branch (for example, the feature branch was finished and you merged it into master using a git merge feature).

The push is denied because it turns out that the remote master (origin/master) moved. You then must do a pull before continuing. If this is in rebase mode, that will automatically rebase the recent local history (commits from your old origin/master reference, including your merge commit) on top of the newer origin/master. In a “normal” situation this is fine, but here, it will inline the merge by replacing the true merge with a rebase. The feature branch, until then clearly visible in the log graph, now disappears.

Happily, you can now solve this using the rebase merges option (git pull --rebase=merges or pull.rebase = merges in your configuration).

Better-targeted pushes

By default, git push attempts to publish all your same-name branches to the remote. Whilst I very rarely have new work on multiple branches locally that are tracked on the remote, and thus need this, I do regularly run into the following scenario:

- I need to collaborate on the

featurebranch for a while: Igit switch feature, which sets up a local branch tracked on the remote one. - I work, I commit, I push, everything works…

- After a while, either I’ve only been working on

featurefor a while and mymasterfalls behind the remote, or I’m done withfeatureuntil further notice, switch back tomasterand after a while my localfeaturefalls behind the remote.

At that point, every push will balk, rejecting the lagging branch(es). It’s quite annoying, because I’m not actually trying to push those branches, I just have them locally and will probably work on them again later. This is the matching mode, which as the doc says is not appropriate for a multi-developer environment, but was (until Git 2.0 anyway) the default mode.

By setting push.default to upstream, I change the default behavior of push so that it only cares about the active branch. This is a more flexible variant of simple mode, which would require the local and remote branches to be not only connected (tracking) but homonymous. Note that this simple mode has been the default mode since Git 2.0.

Wrapping up…

Well, that’s a good thing done! Remember to look at the release notes when you update your Git, and especially to look at the git help config section from time to time, which lists all the available settings, or simply to see if the git help section of your current command doesn’t provide a CONFIGURATION section at the end, which details the relevant settings. You always learn a lot…

Good config to all!

More tips and tricks?

We’ve got a whole bunch of existing articles and more to come. Also check out our 🔥 killer Git training course: 360° Git!