Fix conflicts only once with git rerere

Published on 4 November 2014

• 8 min

Cette page est également disponible en français.

So you fixed a conflict somewhere in your repo, then later stumbled on exactly the same one (perhaps you did another merge, or ended up rebasing instead, or cherry-picked the faulty commit elsewhere…). And bang, you had to fix that same conflict again.

That sucks.

Especially when Git is so nice that it offers a mechanism to spare you that chore, at least most of the time: rerere. OK, so the name is lousy, but it actually stands for Reuse Recorded Resolution, you know.

In this article, we’ll try and dive into how it works, what its limits are, and how to best benefit from it.

The usual suspect: control merges

A situation where rerere comes in really handy is control merges.

Picture this: you’re working on a long-lived branch; perhaps a heavy feature branch. Let’s call it long-lived. And naturally, as time passes, you get more and more apprehensive of eventually merging this branch in the main development branch (usually master), because as time goes by, the divergence thickens…

So to relieve some of that tension and ease up the final merge you’re heading towards, you decide to perform a control merge now and then: a merge of master into your own branch, so that without polluting master you can see what conflicts are lurking, and figure out whether they’re hard to fix.

It is indeed useful, and just so you won’t have to fix these later, you would be tempted to leave that control merge in the graph once you’re done with it, instead of rolling it back with, say, a git reset --merge ORIG_HEAD and keep your graph pristine.

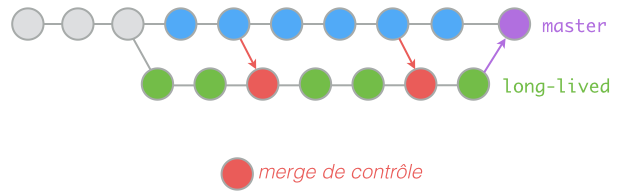

So as time passes, you get a graph that looks like this, but worse:

This is ugly and pollutes your history graph across branches. After all, a merge should only occur to merge a finalized branch in.

But if you cancel that control merge once you’re done, you’ll have to re-fix these conflicts all over again next time you make a control merge, not to mention on final merge towards master. So what’s a developer to do?

rerere to the rescue

This is exactly what rerere is for. This Git feature takes a fingerprint of every conflict as it happens, and pairs it with a matching fix fingerprint when the problematic commit gets finalized.

Later on, if a conflit matches the first fingerprint, rerere will automagically use the matching fix for you.

Enabling rerere

rerere is not just a command, but a transverse behavior of Git. For it to be active, you need at least one of two conditions to be met:

- The

rerere.enabledconfiguration setting is set totrue - Your repo contains a

rereredatabase (you have a.git/rr-cachedirectory)

I can’t quite fathom a situation where having rerere enabled is a bad idea, so I recommend you go ahead and enable it globally:

git config --global rerere.enabled trueA conflict shows up

Let’s say you now face a conflict-bearing divergence; perhaps master changed your <title> in index.html a certain way, and long-lived did otherwise.

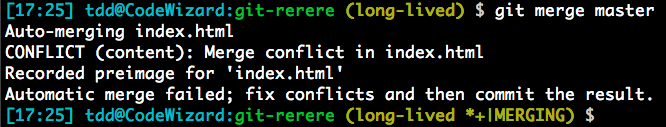

Let’s try a control merge:

(long-lived) $ git merge master

This looks like your regular conflict, but do pay attention to the third line:

Recorded preimage for 'index.html'This tells us that rerere lifted a fingerprint of our conflict. And indeed, if we ask it what files it’s paying attention to on this one, it’ll tell us:

(long-lived *+|MERGING) $ git rerere status

index.htmlIf we look into our repo, we’ll indeed find the fingerprint file:

$ tree .git/rr-cache

.git/rr-cache

└── f08b1f478ffc13763d006460a3cc892fa3cc9b73

└── preimageThis preimage file contains the full fingerprint of the file and its conflict (the entire blob, if you will).

Recording the fix

OK, so let’s fix this conflict. For instance, I’ll go with the following combined title:

…

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<title>20% cooler and more solid title</title>

</head>

…I can then verify what rerere will remember once I complete the merge:

$ git rerere diff

--- a/index.html

+++ b/index.html

@@ -2,11 +2,7 @@

<html>

<head>

<meta charset=”utf-8">

-<<<<<<<

- <title>20% cooler title</title>

-=======

- <title>More solid title</title>

->>>>>>>

+ <title>20% cooler and more solid title</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Base title</h1>I can then mark this as fixed the usual way, with a git add. Then git rerere remaining will tell me what other files I should look into (right now, none).

At any rate, for rerere to effectively remember the fix, I need to finalize the current commit. This being a merge, it falls to me to manually perform the commit:

(long-lived +|MERGING) $ git commit --no-edit

Recorded resolution for 'index.html'

[long-lived fcd883f] Merge branch 'master' into long-lived

(long-lived) $Pay attention to the second line:

Recorded resolution for 'index.html'And indeed, that fix snapshot is now a postimage in our repo:

$ tree .git/rr-cache

.git/rr-cache

└── f08b1f478ffc13763d006460a3cc892fa3cc9b73

├── postimage

└── preimageSo I can go right ahead and roll back that control merge, because I don’t want to pollute my history graph with it:

(long-lived) $ git reset --hard HEAD^

HEAD is now b8dd02b 20% cooler title

(long-lived) $The conflict re-emerges

Let’s now assume that long-lived and master both keep marching on. Perhaps in the former, a CSS comes up. And in the latter, the same CSS appears (albeit with different contents), along with a JS file.

The time comes when a new control merge seems in order. Here we go:

(long-lived) $ git merge master

Auto-merging style.css

CONFLICT (add/add): Merge conflict in style.css

Auto-merging index.html

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in index.html

Recorded preimage for 'style.css'

Resolved 'index.html' using previous resolution.

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

(long-lived *+|MERGING) $We have an add/add conflict for the CSS, and the well-known conflict for index.html. But look more closely around the end:

Recorded preimage for 'style.css'

Resolved 'index.html' using previous resolution.As you can see, the conflict about index.html is known already, and has been auto-fixed. Indeed, if you ask git rerere remaining what’s up, it’ll tell you that only style.css is still in trouble.

So let’s start with marking index.html as being okay, by staging it:

$ git add index.htmlBy the way, if you prefer rerere to auto-stage files it solved (I do), you can ask it to: you just need to tweak your configuration like so:

$ git config --global rerere.autoupdate trueFrom now on, I’ll consider you have this setting on. As we did before, let’s fix the remaining conflict, and then:

(long-lived *+|MERGING) $ git commit -a --no-edit

Recorded resolution for 'style.css'.

[long-lived d6eea3e] Merge branch 'master' into long-lived

(long-lived) $We now have two pairs of fingerprints available, including one on style.css:

$ tree .git/rr-cache

.git/rr-cache

├── d8cd8c78a005709a8aac404d46f23d6e82b12aee

│ ├── postimage

│ └── preimage

└── f08b1f478ffc13763d006460a3cc892fa3cc9b73

├── postimage

└── preimageAnd we can roll back that commit, like before.

To wrap up, let’s assume index.html gets modified one last time, adding contents near the end of the <body>. Then we commit it.

This was the last necessary commit for long-lived, so instead of doing yet another control merge, we decide to do the final, proper merge into master:

(master) $ git merge long-lived

Auto-merging style.css

CONFLICT (add/add): Merge conflict in style.css

Auto-merging index.html

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in index.html

Staged 'index.html' using previous resolution.

Staged 'style.css' using previous resolution.

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

(master +|MERGING) $Note that instead of the “Resolved… using previous resolution” we had before, we now get:

Staged 'index.html' using previous resolution.

Staged 'style.css' using previous resolution.This is because we asked rerere to auto-stage completely fixed files. And indeed, my prompt only mentions “+” (staged), no “*” (modified), which leads me to think that there’s no remaining conflict. Something git rerere remaining confirms by not showing anything.

So you don’t need to stop when seeing “Automatic merge failed” at the end, this only means that regular merge strategies were not enough; but because we had rerere help out on top of it, we could go through. Still, because rerere heuristics are not 100% guaranteed to be relevant (the context might have changed…), Git will refuse to auto-finalize a rerere-helped operation.

To make sure it was adequately fixed, if you have any doubt, a simple git diff --staged or git show :0:file (that’s a zero, not an O letter) will calm your fears.

It still is your job to wrap up the commit:

(master +|MERGING) $ git commitContext-free

You should remember that the fingerprints are independent of context:

- It doesn’t matter which command resulted in the fingerprint pair being lifted (

merge,rebase,cherry-pick,stash apply/pop,checkout -m, etc.). - It doesn’t matter which command re-uses the fix.

- It doesn’t matter what paths the conflicting files were at (it’s the snapshot’s contents that matters).

On the other hand, a fingerprint is usable only if its diffs’ immediate contexts are preserved, as is usual for merge conflicts. If you modified a line too close to a diff in the preimage, rerere will refuse to consider that image+fix pair, and you’ll have to fix the new context yourself.

Besides, if a new conflict appears in a file that is already targeted by fingerprint pairs for previous conflicts, rerere seems quite strict about its rules of applicability for previous fixes. I find it hard to determine just what its proximity thresholds are, but it may well ignore previous fixes and decide to ask for a new fix for the entire conflict set in the file. As usual, YMMV.

Can’t I share this with other contributors?

Just like hooks, the rerere database (the .git/rr-cache directory) stays in your local repo: it’s not shared with upstream when you push (regardless of your push settings and options).

And just like hooks, this doesn’t mean you can’t share these with co-workers and fellow code contributors if you really want to (it’s actually a rather good idea to share these). There are several options, usually based on symbolic links (symlinks).

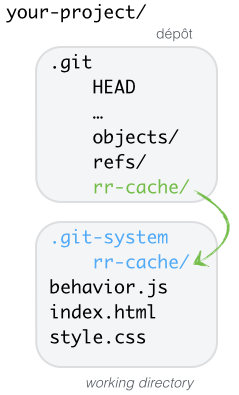

Option 1: embedded in your working directory

You can absolutely dedicate a directory in your WD to sharing elements otherwise kept local in your repo, such as rr-cache and hooks, for instance.

You could create a directory named .git-system at the root of your WD, in which you’d have subfolders. This way in your .git directory, rr-cache would be a symlink on ../.git-system/rr-cache. On OSX / Linux / Git Bash, you’d do it the following way:

# Create the folder

mkdir .git-system

# If your folder exists in the repo, move it;

# otherwise create it at its final location

[ -d .git/rr-cache ] && mv .git/rr-cache .git-system/ ||

mkdir .git-system/rr-cache

# Create the symlink

ln -nfs ../.git-system/rr-cacheOn Windows, this would look more like this:

mkdir .git-system

if exist .git\rr-cache (move .git\rr-cache .git-system) else mkdir .git-system\rr-cache

mklink /d .git\rr-cache ..\.git-system\rr-cache(Since Windows Vista, the mklink command lets you create symlinks, but you’ll have to run it in an elevated-privileges command prompt, that is, one ran as administrator. Your being admin is not enough. OR, your Local Security Policy could include your specific user account in the Create Symbolic Links authorization. Because, you know, symlinks are for evil hackers, right?! More info on mklink here. If on Windows XP or not wanting to get hurt with Windows scripting, just run the first set of commands in the Git Bash installed by your Git Windows installer.)

In such a situation, the idea is not to include the new fingerprints in the original fix commit, keeping .git-system contents in its own commit. This requires some juggling with the fact you want to reset control merges, but keep the fingerprints-only later commit. A three-point rebase helps with that, for instance:

# 1. Ensure you're not committing .git-system by mistake

(long-lived *+|MERGING) $ git reset -- .git-system

(long-lived *+|MERGING) $ git commit --no-edit

# 2. Commit .git-system by itself

(long-lived *) $ git add .git-system

(long-lived +) $ git commit -m "Fix fingerprints for control merge"

# 3. Rewrite history to preserve only the last of the 2 commits.

(long-lived) $ git rebase --onto HEAD~2 HEAD^Option 2: a dedicated local-sharing repository

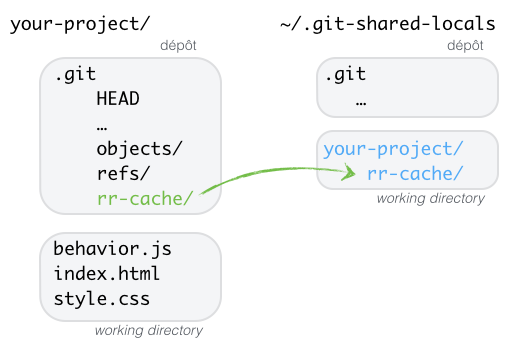

The other approach, which avoids commit juggling but makes sharing a two-step process, is to have a repo (and its upstream for sharing, obviously) dedicated to sharing settings otherwise kept local.

You’d only change the target of your symlink to something more fixed and absolute, ideally a subdirectory of your central sharing repo, something along the lines of:

~/.git-shared-locals/your-project/rr-cacheon OSX/Linux, orC:\Users\you\git-shared-locals\your-project\rr-cacheon Windows.

In that manner, you do not introduce any extra contents in your working directory due to fingerprinting. No commit juggling. It’s just that, to share your fingerprints you’d need to also go to the central sharing repo, commit these, do a quick git pull --rebase to get whatever shared configs are new on the server and replay your own new stuff on top of it, then git push to actually share with your friends.

(This is the second time we’re talking about rebasing in this article; if you’re confused about when to merge vs. rebase, and what odd things like three-point rebases are, we’ve got you covered).

This is two-step, but eliminates the risk of broken commits mixing preimage fingerprints with fixes, etc.